The region was claimed by the Spanish Empire in the late 18th century. Most of the Coast Miwok were taken into the Franciscan missions in San Francisco and points south. Some returned to the area with the building of Mission San Rafael Archangel in 1817, but many died of European disease, became part of the mission and rancho system, or escaped to areas outside foreign control.

The first English-speaking farmer, John Reed, arrived in 1826 in the territory of the Kota’ti-Bloomfield band, but found that raising wheat near Crane Creek where the Coast Miwok set seasonal fires was a losing proposition. (He soon established a rancho in southern Marin County, where he founded Mill Valley.) The tribe held on for a while longer, but maintaining traditional ways in the face of invasion became unsustainable.

In 1844, the Mexican government (established in 1823) granted four square leagues (17,238 acres, stretching from what is now Penngrove to Santa Rosa) to Captain Juan Castañeda for his military service. In 1846, Castañeda sold the property to U.S. Consul Thomas O. Larkin. Larkin sold it to broker Joseph S. Ruckle, who held it for only two months before selling it to Dr. Thomas Stokes Page in 1849, a native of New Jersey, then living in Valparaiso, Chile. In 1850, California became the 31st of the United States, and a new era began for the Rancho Cotate.

After nearly a decade of wrangling over Spanish, Mexican, California, and U.S. land law, Dr. Page’s agents purchased livestock, constructed ranch buildings, and began farming for the absentee landlord, as well as selling off portions of the rancho to Americans and European immigrants. In 1869, Dr. Page, his wife, Anna Maria Liljevalch Page, and their four youngest children emigrated from Chile, and set up housekeeping in San Francisco. Dr. Page died in 1872, leaving the management of the sprawling dairy, livestock and grain farm to his oldest sons. In 1874, the ranch, still 10,000 acres was valued at $1 million. Because of a clause in Dr. Page’s will that the balance of the ranch remain intact until his youngest child reached 25 years of age, Cotate was one of the last great California land grants to be subdivided, in 1892.

Wilfred, the middle Page son and resident manager of the rancho, with the help of local surveyor Newton Van Vliet Smyth, platted the new town with farms of five to 20 acres, as well as smaller villa and commercial lots surrounding a hexagonal central plaza. The six-sided plaza and an outer concentric set of hexagonal streets named after Wifred’s six brothers (Olof, Henry, Charles, Arthur, George, and William) are so unusual as to have been named California Historical Landmark No. 879.

Incidentally, the Page sisters, Anita, Lizzie, and Manuela still await the honor of having streets named after them. For himself, Wilfred named what he expected one day to be a major thoroughfare: Wilfred Avenue, several miles to the north. It now lies within Rohnert Park’s city limits and fronts the Graton Resort & Casino (as Golf Course Drive West). Other Cotati street names refer to Page family connections: Page Street; Valparaiso Avenue, named after the family’s previous home; Delano Street, named after Mrs. Page’s maternal family line; and El Rancho Drive, where the Page mansion built in 1878 stood until it burned in the 1930s. Why the central hexagon —which mirrored the ranch’s long ago barn, watering trough, and mansion tower—was important to the Page family remains a modern mystery.

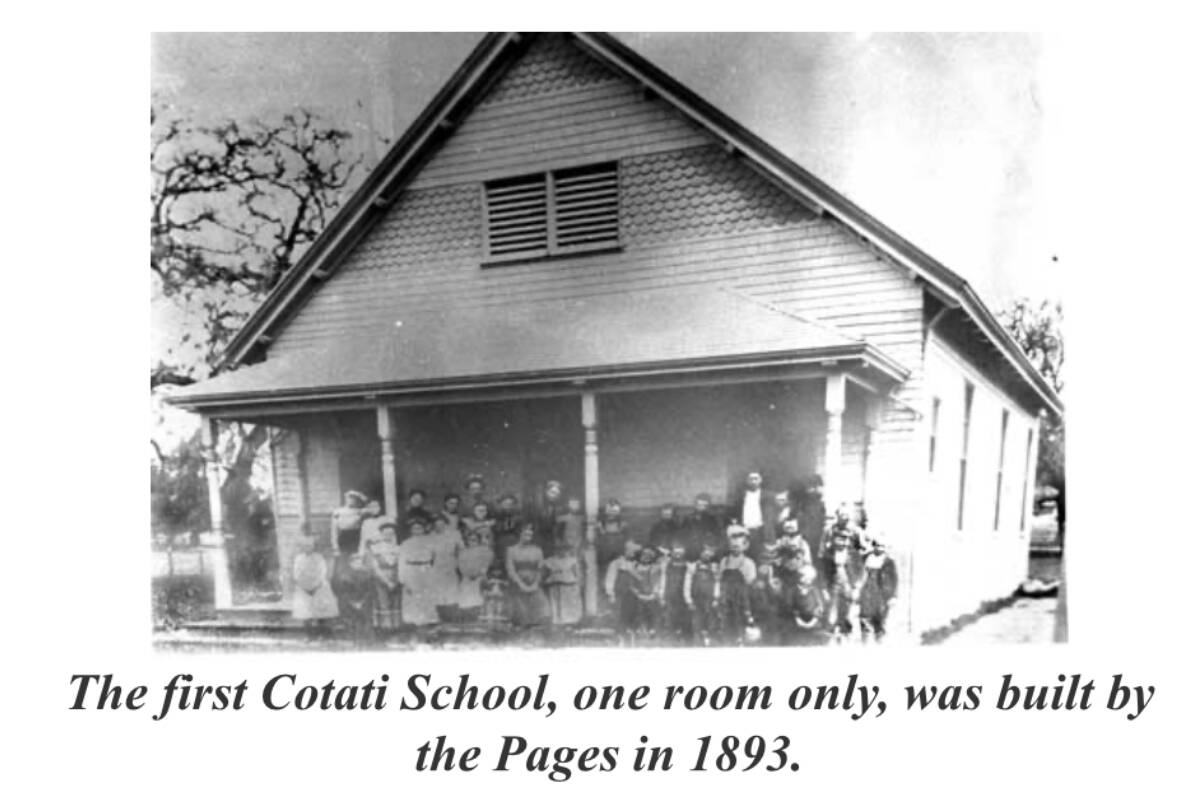

It was also in 1892 that Cotate became “Cotati,” due to the tendency of strangers to mispronounce the Spanish name. The newly formed Cotati Land Company, managed by the Page brothers and Lizzie’s husband, John Mailliard, began selling lots in 1893. Railroad travelers arriving at or passing through Page’s Station on East Cotati Avenue could not miss the large signs offering ranch land at low prices and easy terms. Real estate salesman salesmen David Batchelor and others worked with the Pages to help new landowners establish chicken ranches and other rural businesses. In the 1930s, what was left of the family property became the Waldo Rohnert Seed Co., and eventually the city of Rohnert Park, incorporated in 1962.

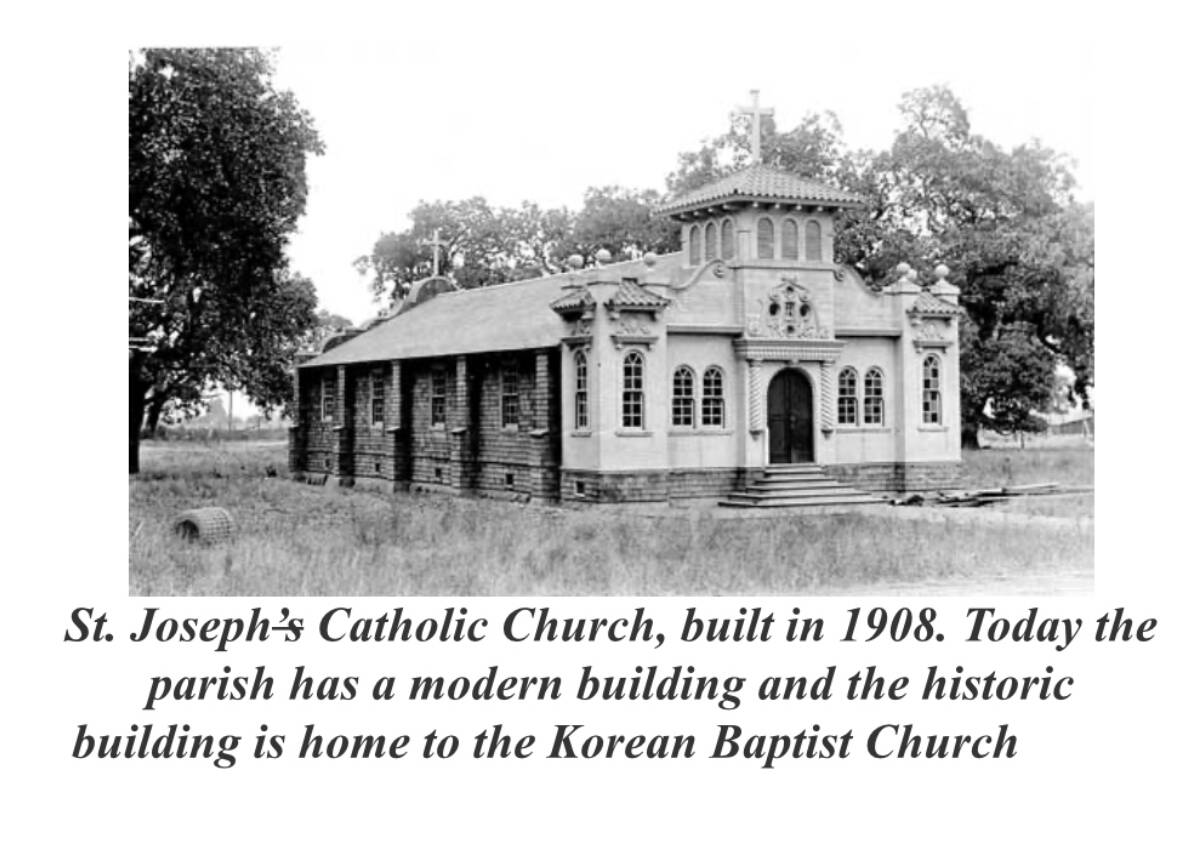

The founders established a post office and school in 1893 and the new Cotati folk got right down to forming a community. By the early 1900s they had built a Congregational Church (now Church of the Oaks), a Catholic Church (St. Joseph’s, now the Korean Baptist Church), and a social hall for the Cotati Women’s Club (now Congregation Ner Shalom). The Odd Fellows Hall (now the home of Loud and Clear Music) and numerous stores sprang up around the Plaza to serve the surrounding agricultural area.

In 1915, the Plaza became a regional landmark when the state of California opted to run the Petaluma-Santa Rosa Highway through the middle of Cotati. Local merchants enjoyed the automobile traffic coming through town and generating previously unimagined business. Garages, auto dealers, and restaurants rose up between the farm supply and general stores that had previously constituted Cotati’s business district.

In the 1920s, Cotati formed a Volunteer Fire Department, an American Legion Post, and a renowned baseball team, sponsored by the town pool hall owner. Speculators developed an immense wooden auto racetrack near the railroad tracks on East Cotati Avenue, and drivers and fans converged from far and wide. The opening race at the Cotati Speedway attracted 20,000 spectators; and internationally known drivers broke world speed records. This was, however, prior to the completion of the Golden Gate Bridge (1937) and the trip required a series of ferry and railroad connections. Not enough fans could manage the trip over a full race season and the track was soon declared a financial failure. The lumber salvaged from its demolition produced several of the buildings still in use in downtown in Cotati and around the county.

Cotati’s population of self-sufficient small farmers and business-people weathered the Great Depression well enough. But after World War II, the chicken business began to change from small family farms scattered along dotting the north coast to large agribusinesses in California’s central valleys. Many small landholders left off farming and sold their lands for new home construction and modern businesses. Cotati, still unincorporated, established a Public Utility District in the early 1950s to provide sewer and water service; the county sheriff addressed public safety concerns; and the Chamber of Commerce served as the community’s prime force in making improvements. The Chamber’s Plaza-improvement projects included a number of memorials and monuments to local individuals and causes. The many statues for which contemporary Cotati is becoming known arose after Cotati became a city.

That momentous event occurred in 1963 when the independent little community felt threatened by burgeoning Rohnert Park, a fully planned bedroom community incorporated in 1962. To retain its identity and rural lifestyle, Cotati finally incorporated. As a proper municipality it began to take more responsibility for its own destiny experimenting with a number of civic forms before settling on the current city manager/city council arrangement.

In the 1970s, students from the nearby and newly founded Sonoma State University took a special liking to traditional Cotati with its rustic lifestyle and initiated bold changes in the city’s philosophy and scenery. Along with local hippies, they converted the old Cotati Inn restaurant into The Inn of the Beginning and featured world-class artists, playing rock, blues, and other genres. The La Plaza Park became a social center with a volunteer-built bandstand and almost continuous popular use to the joy of the younger citizens and dismay of the oldsters. Artist and performer Vito Paulekas created the Plaza’s first statue, a fanciful, cement-composite-and-glass depiction of the fictional Chief Kotate, arms upraised in Native ceremonial dance.

In 1991, the first Cotati Accordion Festival resounded in La Plaza. Founded by local musicians, the festival became a hit with musicians, polka dancers, and other lovers of Lady of Spain from around California and beyond. Bandleader and accordionist Jim Boggio was one of its stars. In 1997, after Boggio’s unexpected death, a cast bronze statue by Jim Kelly of the musician with an accordion was added to the Plaza scene. There are now multiple art and memorial installations and gardens scattered throughout this iconic public space.

Today, Cotati is a fully-fledged city with an efficient form of government, independent police department, and public works, community development, and recreation departments, planning and building departments and a active citizens’ planning commission.

The downtown’s general stores of the past have given way to sidewalk cafes and restaurants, salons, and shops, and former farmland on the west side of town is home to industrial and business parks. But Cotati denizens remain as independent and forward-thinking as those early small-farm owners and business people who created the charming and quirky, artistic and musical, country-town energy that Cotati continues to pour forth.